(Better)'

how might we encourage incremental change to bring sustainable practices to fashion factories?

Mansi Gupta’s thesis titled “BETTER: The prejudices & practices of mass production” began with one goal: to bring sustainability to the larger fashion system, especially the factories. For decades, the fashion industry has been criticized for having a negative social and environmental impact through its production practices. As a response, a green fashion trend, recently known as “sustainable fashion”, emerged in the form of small brands, marketplaces and protests against fashion factories. Using the ideas of sustainable fashion as inspiration, Gupta wanted to devise ways that sustainable production methods could be adopted by factories as well.

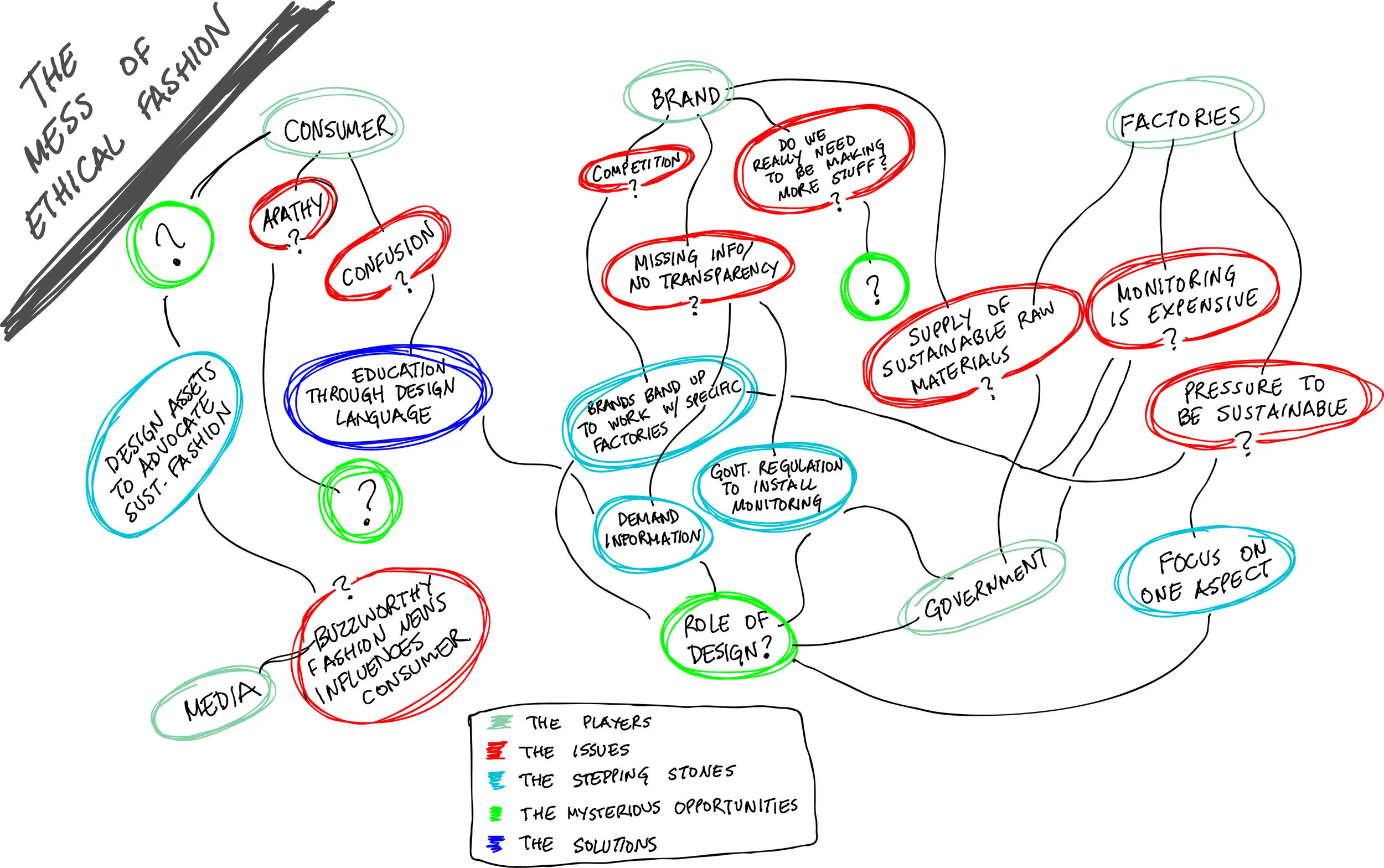

Gupta was really intervening in a large and complex system; this realization came about as she began speaking with various experts in the field to understand the many issues, challenges and language of sustainability. After every expert provided her a different definition of sustainability, and their opinion on the most urgent challenge, Gupta began to see the fashion production and sustainability as a complex system of many stakeholders -- and decided she must define sustainability herself.

Inspired by Shona Quinn of Eileen Fisher, Gupta defined sustainability as continuous incremental change and created (BETTER)’, a platform and ecosystem that spoke to factories, consumers, producers and brands. (BETTER)’ began as an accessible labeling and certification system for factories that were producing product using a ‘better’ method of production. It was an education platform for all stakeholders of the system. It also served as a crowd-voting and storytelling space - for factories to tell their stories, for for consumers to have a voice and support sustainable initiatives that they wanted to see come to life.

The (better)' service

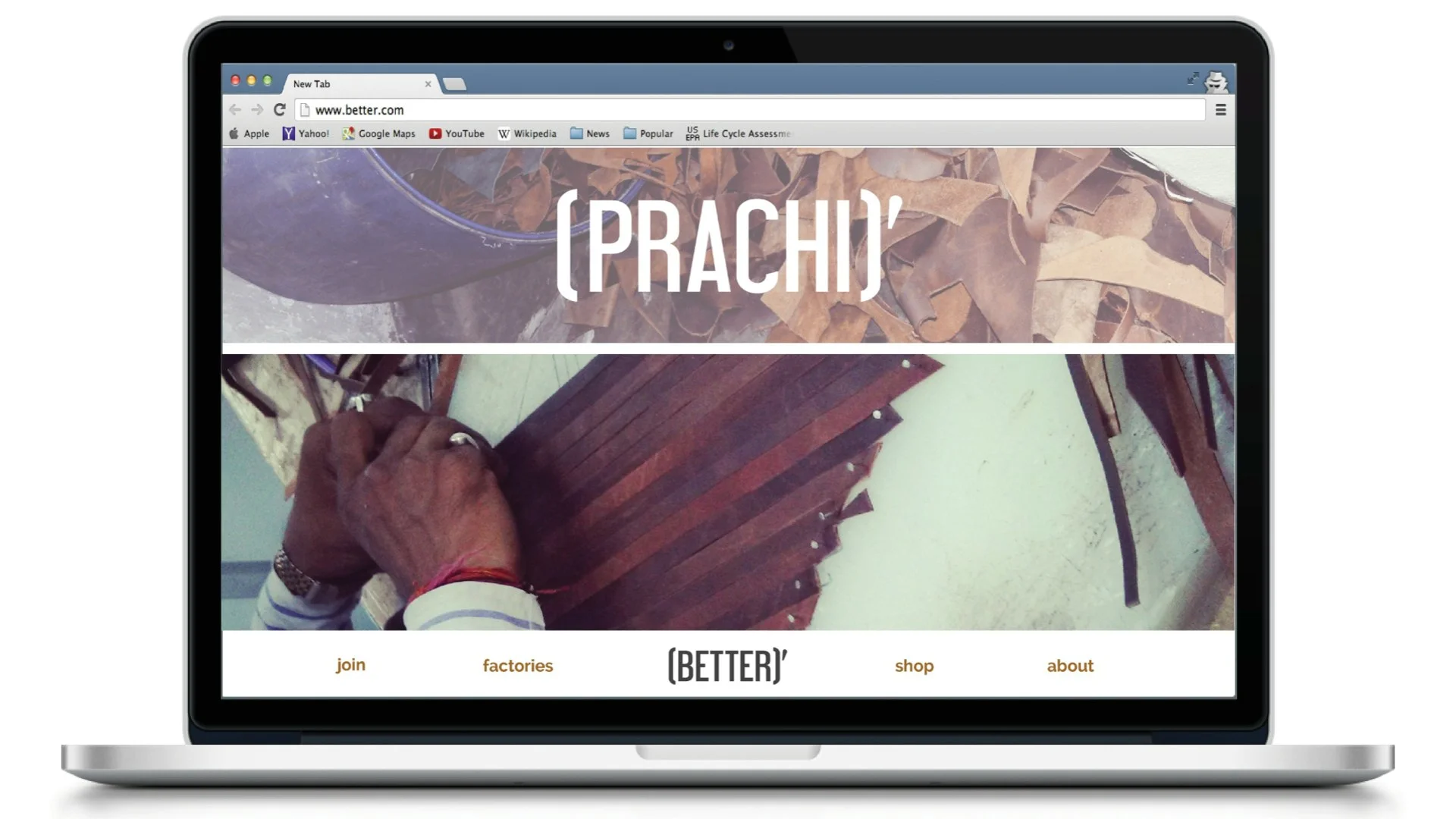

Gupta further developed (BETTER)’ as a service. Factories are not necessarily aware of the importance to be more sustainable or transparent. Moreover, they do not know how or have the means to be more sustainable and transparent. In response to this realization and that most production takes place in factories, Gupta chose factories as her core audience for the service. (BETTER)’ came from the insight that there is an emerging demand for stories about where our things come from, or where our things are made, that most of our things are made in factories, but factories don’t know how to tell these stories, or they might not have any proud stories to tell. (BETTER)’ is a service that creates a story that factories will want to tell, by unveiling business opportunities in the factory’s existing system through experimentation, branding and storytelling.

(BETTER)' the service, a multi-tiered platform for improving production practices and increasing transparency in factories, seeks to transform the stigma surrounding manufacturing that sees factory work as monotonous, devalued, and unsustainable. (BETTER)' seeks to undertake this work on a number of levels-- economic, systemic, practical and social. On an economic level, (BETTER)' would help the factory find a business opportunity that results from the adoption of a better production practice.

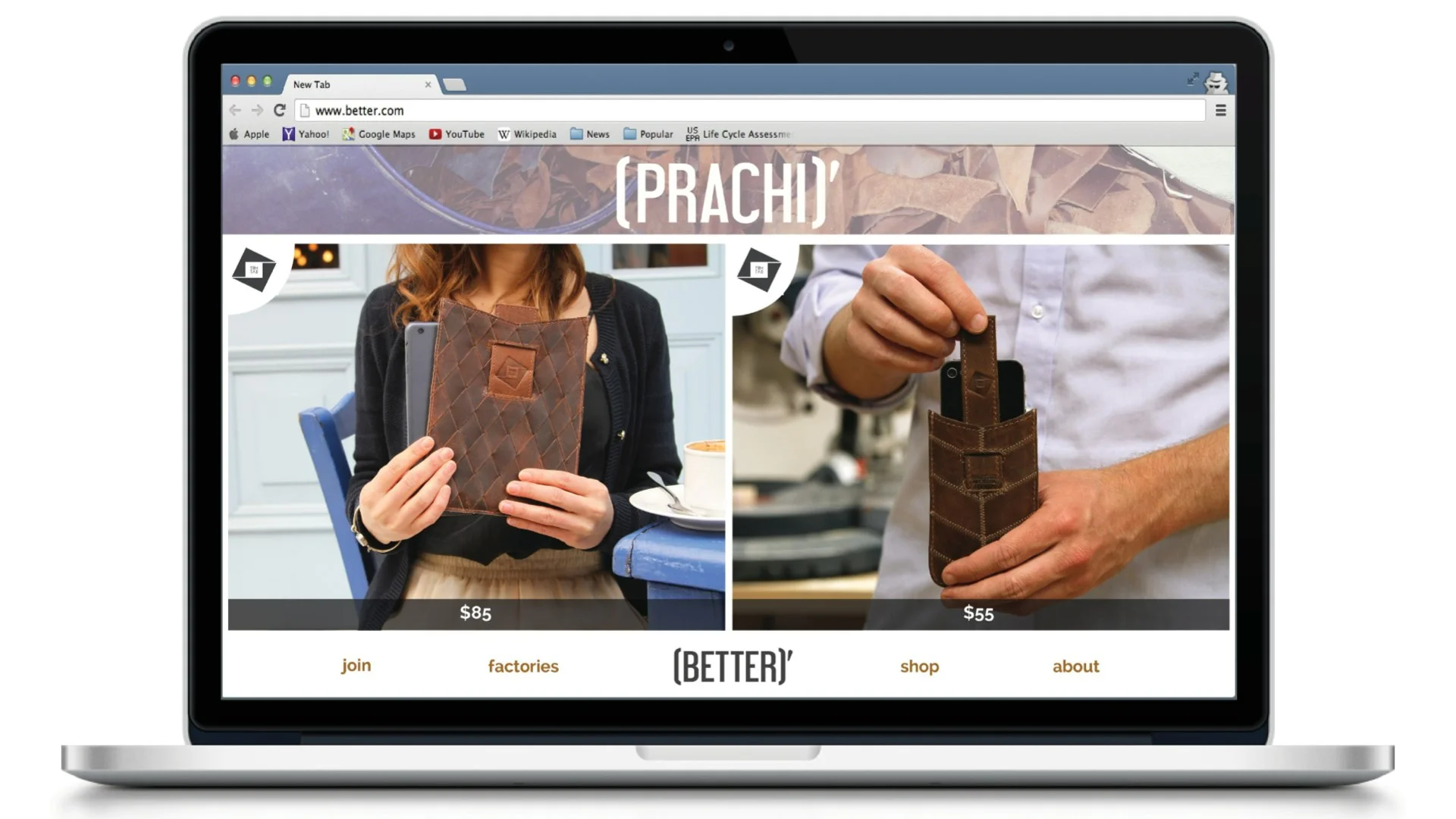

Changing or introducing a new production practice included switching costs, and (BETTER)' understands the importance of providing a way of financially supporting the changes through a new revenue stream. (BETTER)' is also cognizant of the fact that factories may not necessarily know how to market their new business opportunity or product, and thus provides a marketplace to help them kickstart their product / new business venture.

On a systemic level, (BETTER)' suggests changes and business opportunity to factories within their existing system so that it no only seems feasible, but also involves changing an existing practice to a slightly better one.

On a practical level, (BETTER)' suggests the system intervention to the factory as an experiment. (BETTER)' realizes that the change will require some prototyping and re-iteration in order to be successful, and by framing the change as an experiment at first, (BETTER)' creates room for time as well as failure.

On a social level, (BETTER)' would play the role of helping the factories tell their stories of small changes in an effort towards transparency. (BETTER)' will do this through their marketplace which will also serve as an ecommerce platform where consumers can financially support the factories by buying factory products after learning the story of how it was made, where it was made and who it was made by.

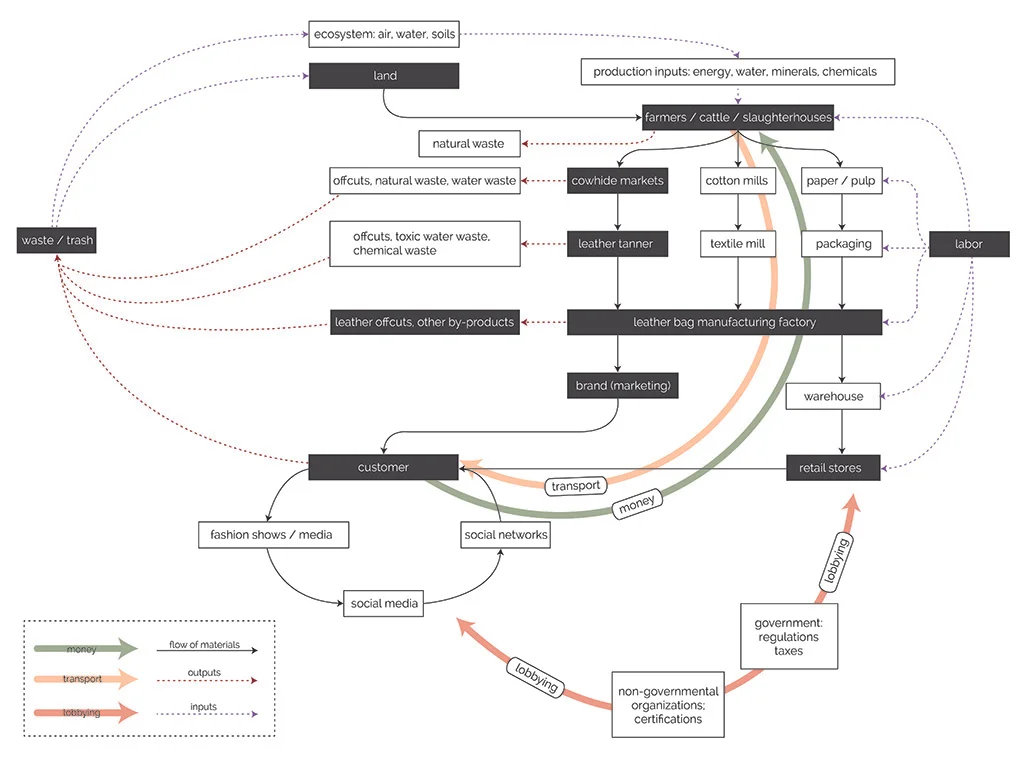

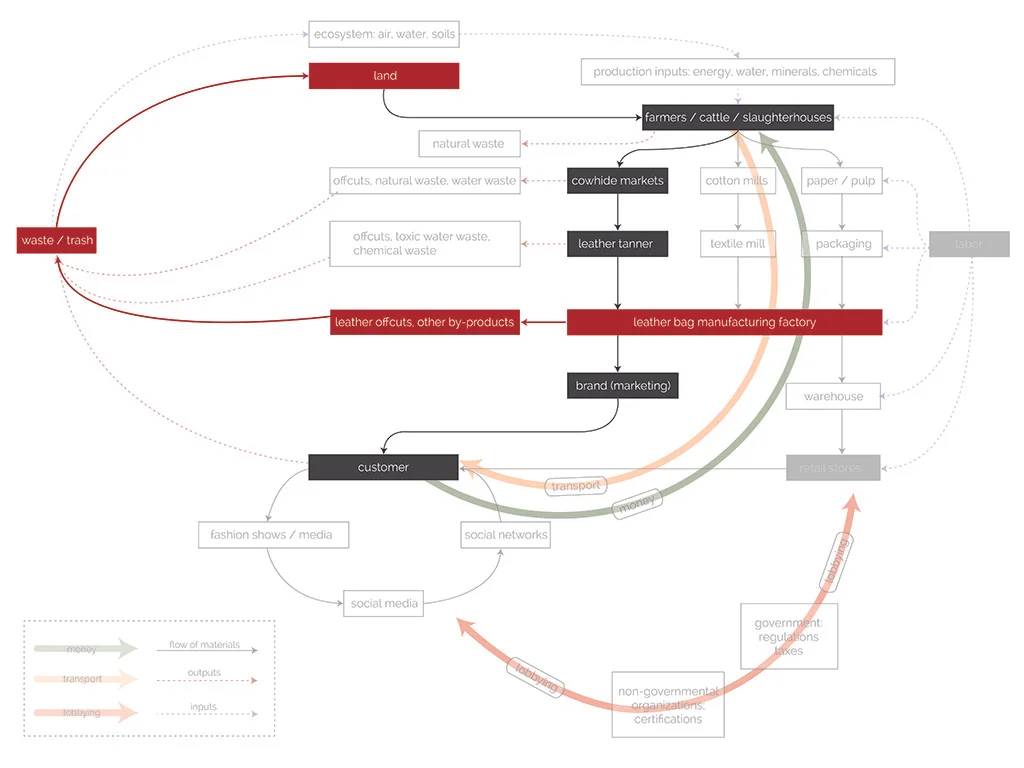

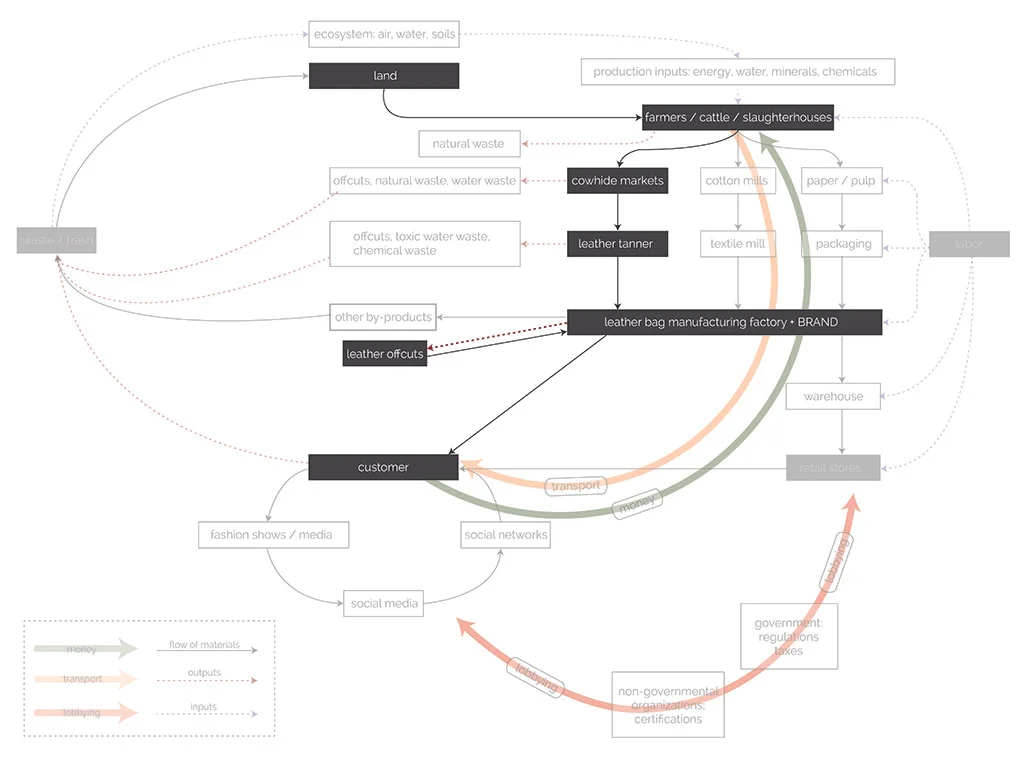

(BETTER)’ was prototyped with Prachi Leathers, a leather factory and tannery located in Kanpur, India. A visualization of the existing system at Prachi helped to identify a story that producers would want to hide and (BETTER)’ transformed it into one that they would want to tell. Identifying leather scraps, which result from the factory’s everyday production and usually end up in landfill, as a story that they would want to hide served as a fitting opportunity to prototype an initial small change. Working with the factory’s sample team, (BETTER)’ brainstormed ways in which the scraps could be put to use. Because of their skill and leather craftsmanship, the sample team turned out to be an asset in this experiment. Through several experiments with the sample team, (BETTER)’ and Prachi created a line of upcycled leather goods by stitching and weaving together the leather remnants. Worker voices told the story of Prachi and their process of creating a better product from waste material. Collaborating with her colleague Cassandra Michel, Gupta branded the experiment as TRMTAB.

(BETTER)’ was further taken out to the factories in the garment district of New York, and worked with Baikal Handbags. In this collaboration with Baikal, (BETTER)’ served as the platform through which Baikal communicated the complexity and people behind the making, and created a voice for the factory through which it shared its aspirations.

As a final piece, Gupta created a response to the perception of factory workers. Through her year of work and research, she found this perception to often be negative -- many imagine factory workers to be faceless victims of monotony and sadness. She was urged to create ‘The Manufacture Movement’ as a way to appreciate the positives and dignity of factory work in the ways that the workers appreciate it themselves.

Factories are a great first step, Gupta believes. The values of accelerating incremental change, transparency and appreciation can be applied to not only the fashion, but various manufacturing systems as well. Through these steps, Gupta envisions building conversations, experiments, brands and products that will continue and strive to be even better.